Melting tropical glaciers

Segundo Olmedo Cayambe Lema, president of CORDTUCH, the community tourism organisation of the Chimborazo region

© Gustavo Tosello / ISA

“Well, up there, the Yanacocha and the Chaquishkacocha lagoons used to be the watering places for the cattle of the Tambohuasha community. Now, they have disappeared because it is raining less and getting much warmer. The community must pipe water for their cattle from the neighbouring Carihuayrazo mountain. In the past decade, the cattle have had to graze ever-higher up in the Chimborazo Fauna Production Reserve in order to have access to water and the pastures that depend on it.

The last ‘hielero’ of the Chimborazo

Once upon a time, indigenous inhabitants used to extract ice from the Chimborazo upstream of the lagoons and sell it to the townspeople. Today, there is only one ‘hielero’ (ice merchant) left, Don Baltasar Ushca. He told me how it used to be quite cold on the Chimborazo, there was enough rain and the snow remained even down to where the communities live. At 4,000 m above sea level, it was even 40 cm deep. Now, though, the ice only starts at 5,500 m and there is no snow anymore.”

Scientific Background

The smallest glaciers in the Andes, such as the one on Carihuayrazo, located less than 5,100 m above sea level are irremediably out of balance due to the current climate: in the past 80 years, the temperature in thetropical Andes rose by 0.7°C. The frost and the relationship between rain and snowfall determine how much a glacier’s surface melts. The glaciers are currently losing mass and if these conditions continue, residual glaciers will have disappeared entirely in a few years’ time – and latest in two decades.

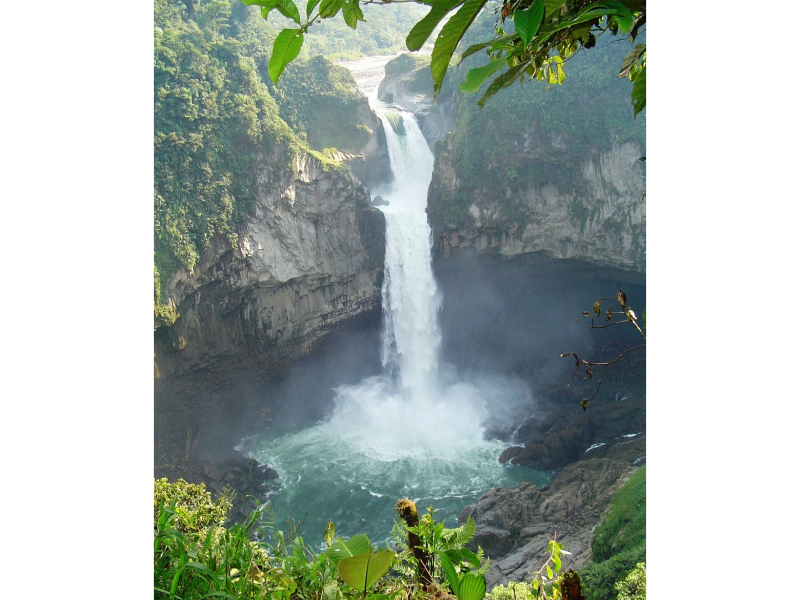

Andean Amazonia: Extreme climate fluctuations

Maria Ushca from Santa Rosa Sector, Santa Clara Canton, in Pastaza Province, Ecuador

© Verónica Angulo, EcoCiencia

“The locals have experienced river floods in recent years that are abnormal for the winter months and suffered some material losses. Although part of the bridge from Santa Clara parish to Tena was damaged in early 2013, the problem was rapidly resolved, as the authorities were already working to replace the town’s sewer system which was far too narrow.”

Scientific Background

The Upper Amazon is located on the eastern slope of the Andes at an altitude of 600– 1,300 m above sea level. High rainfall of 3,000–4,500 mm per year is normal. The temperature ranges between 14 and 24°C, with permanent cloud cover. The volcanic Andean rivers that flow into the Amazon River watershed, such as the Pastaza and the Coca, transport volcanic sediment and supply the lowlands every season. In the Andean foothills, there are increasingly evident alterations in the dry and rainy seasons, with extreme weather events, a decrease in rainfall and an increase in temperature. In 2013, a severe drought led to losses in corn production and consequently to extreme shortages in livestock feed. This affected 1,000 households living at the lowest poverty level. The abnormal climate fluctuations caused prolonged periods of drought followed by heavy rains that led to landslides, floods and disruption to infrastructure and crops that threaten human safety and the Amazon rainforests.