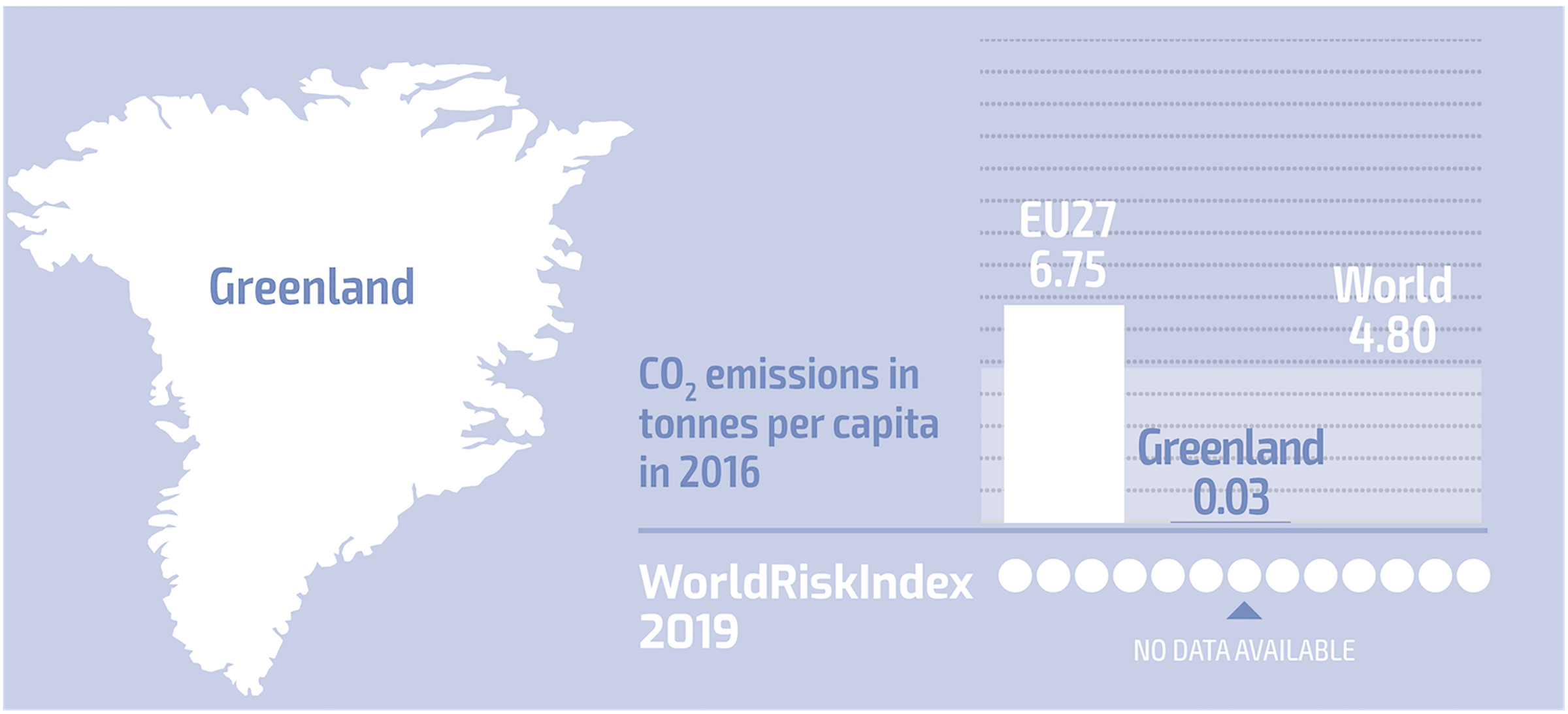

Melting ice

Aqqaluk Lynge, former president of the Inuit Circumpolar Council.

© Inuit Circumpolar Council

Scientific Background

The Arctic climate has changed at an alarming rate over the past fifty years. Arctic glaciers and ice streams are narrowing and flowing at a faster rate. The extent of annual average sea ice has greatly diminished, with scientists predicting that sea ice in the Arctic may disappear entirely by the end of the twenty-first century (IPCC 2007). The decrease in the extent and volume of Arctic Sea ice has exceeded previous projections. Today, the ice is melting seven times faster than it was 27 years ago. In 2011, 2012, and 2014, record low sea ice cover was observed, roughly half the size of the normal minimum extent of the 1980s.

On land and sea

Hunter, close to Ilulissat, on Greenland’s central western coast

© David Trood, Ilulissat 16, flickr /iloveGrönland

“Our ancestors have lived in these vast regions for thousands of years, adapting to one of the most inhospitable climates on the planet, living off the resources that nature provides. When the sea ice grows, you can use that for many things, like transportation. But the sea ice hasn’t been there for the last seven to eight years. You don’t see the sea ice freezing anymore. As the permafrost melts, the roads and airports become unstable, causing damage to infrastructure. We are also experiencing far more violent storms, with hurricane force winds and rains that melt all the snow.”

Inuuteq Holm Olsen, Deputy Foreign Minister of Greenland’s Home Rule Government, Plenty 2008

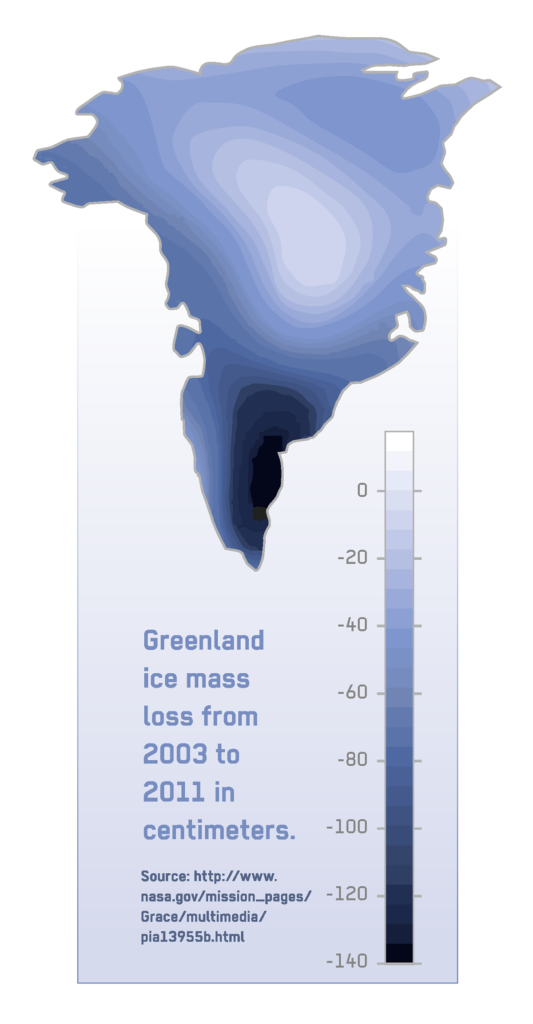

Scientific Background

The Greenland ice sheet is the largest body of ice in the northern hemisphere. It influences the global climate by its direct link to the global sea level and through its effects on ocean temperatures, salinity and circulation. The Greenland ice sheet has been melting at an accelerating rate since the 1990s. In the past 30 years, Greenland has lost around 3.9 billion tonnes of ice. Most recently, the Greenland ice sheet is estimated to contribute up to 10,8 ±0,9 mm1 to the global rise in the sea level each year. Projections foresee a further decrease in the Greenland ice sheet, though the processes determining the rate of melting are still not fully understood. The ‘tipping point’ at which the Greenland ice sheet will melt completely is projected at a global temperature rise of about 3°C, though this estimate is subject to uncertainty.