More intensive rains and floods

Ram Singh and his wife

© Soma Basu/ Down to Earth

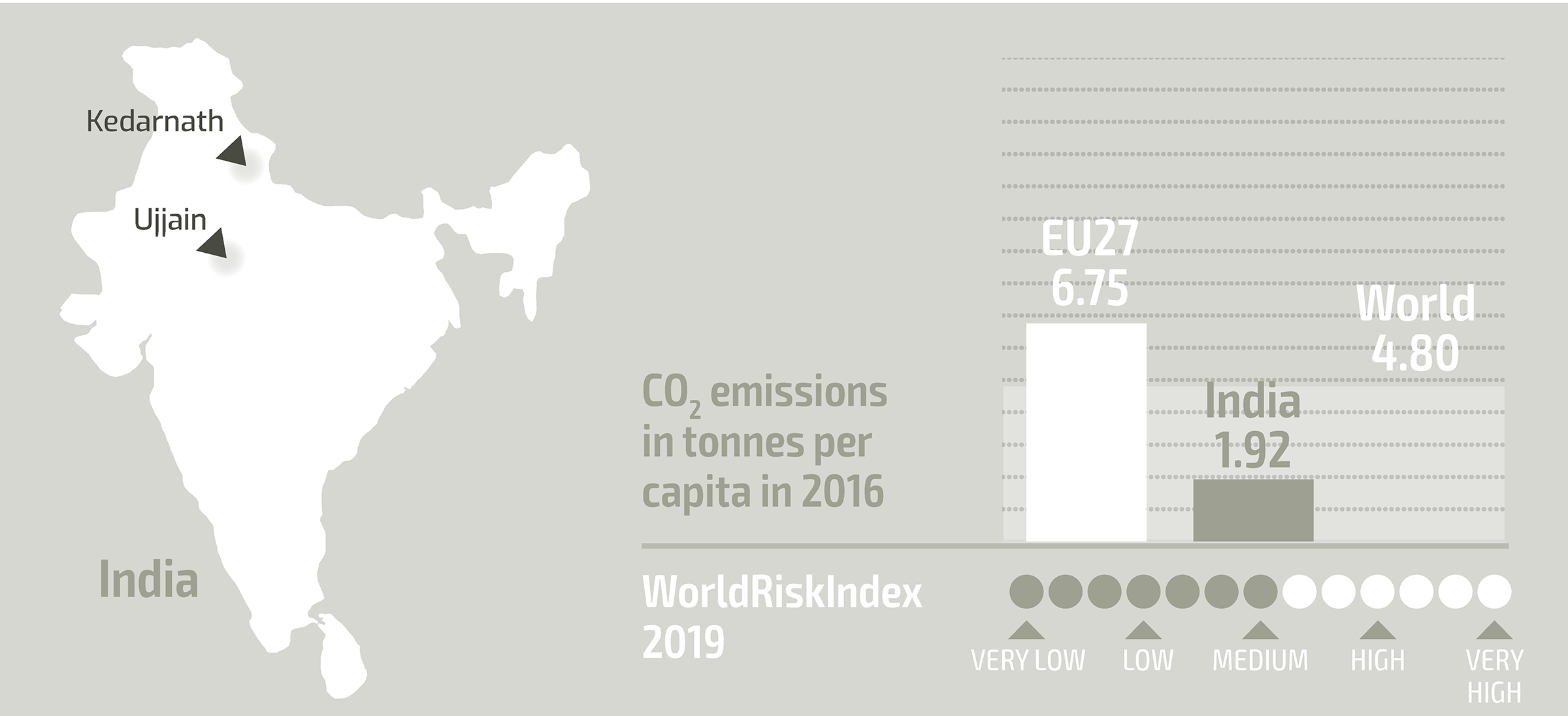

At 7:18 pm on 16 June 2013, Ram Singh heard the loudest crack in his life. It was the deafening roar of a disaster:“I felt as if the sky had been torn asunder. Within seconds, a massive wall of water gushed towards Kedarnath Temple. Huge boulders were flung into the sky like in an explosion. In less than 15 minutes, thousands of people were swept away.” Singh was on a pilgrimage with 17 people from his hometown of Ujjain in Madhya Pradesh. Here turned home with just five of them. “After our visit to the temple, my son wanted to see the hills, so I took him. My wife followed us,” he says. “That’s how we survived. I have no clue where the rest of my family is.”

Scientific Background

The Uttarakhand floods in June 2013:According to Surya Prakash, an associate professor at the National Institute of Disaster Management (NIDM), the abnormally high amount of rain was caused by the fusion of Westerlies with the monsoonal cloud system. Additionally, a huge quantity of water was probably released from the melting of ice and glaciers due to high temperatures during May and June, which led to the breaching of moraine-dammed lakes. Several hundred people were killed; thousands are still missing. Further severe flooding has occurred every year since.

Changing monsoon patterns in India: A trend analysis by Professor S.K. Dash, Head of the Centre for Atmospheric Sciences at the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi, shows that between 1951 and 2000, India witnessed short spells of heavy-intensity rainfall – lasting less than four days – during monsoons and fewer long spells with moderate rainfall. Having collected rainfall data from 2,599 stations between 1901 and 2005, scientists from the India Meteorological Department (IMD) warn of an increased flood risk across most parts of India: “An increasing flood risk is now recognised as the most important sectoral threat from climate change.” (Current Science, June 2013).

Ladakh – flash floods

A house in Leh, destroyed by flooding

© Ladakh Art and Media Organisation(LAMO)

August 2010. A huge flood ravages Leh, killing 257 people in the district, injuring thousands, and destroying property, infrastructure and livelihoods. The flood was the result of very heavy rain falling over a small area. There were other factors: bright sunshine in June and July melted the snow faster than usual, leading to greater humidity. The temperature remained low, which caused dense clouds to form at a low altitude. As these clouds moved over the glaciers, they condensed further, resulting in cloudbursts. Cloudbursts and thundershowers as they have never seen before in Ladakh caused flash floods in almost all of the valleys along the Indus river in Leh district.

Regional context and background

Ladakh is located on the northwestern side of the Himalayas, flanked by four mountains ranges, namely the Himalaya, Zanskar, Ladakh and Karakoram, with extremely high, snow-capped peaks. These mountain chains and the Tibetan plateau are home to 45,000 individual glaciers, covering an area of 90,000 km2. Sometimes referred to as the “water tower of Asia” or the “third pole”, they are the biggest freshwater store outside the polar caps and feed the major rivers in Asia. But the Himalayan glaciers, the source of water for billions, are retreating faster than the glaciers in any other part of the world (Cruz et al., 2007. Source: NASA EROS Data Center, 9 September 2001).

Evidence of climate change in Ladakh

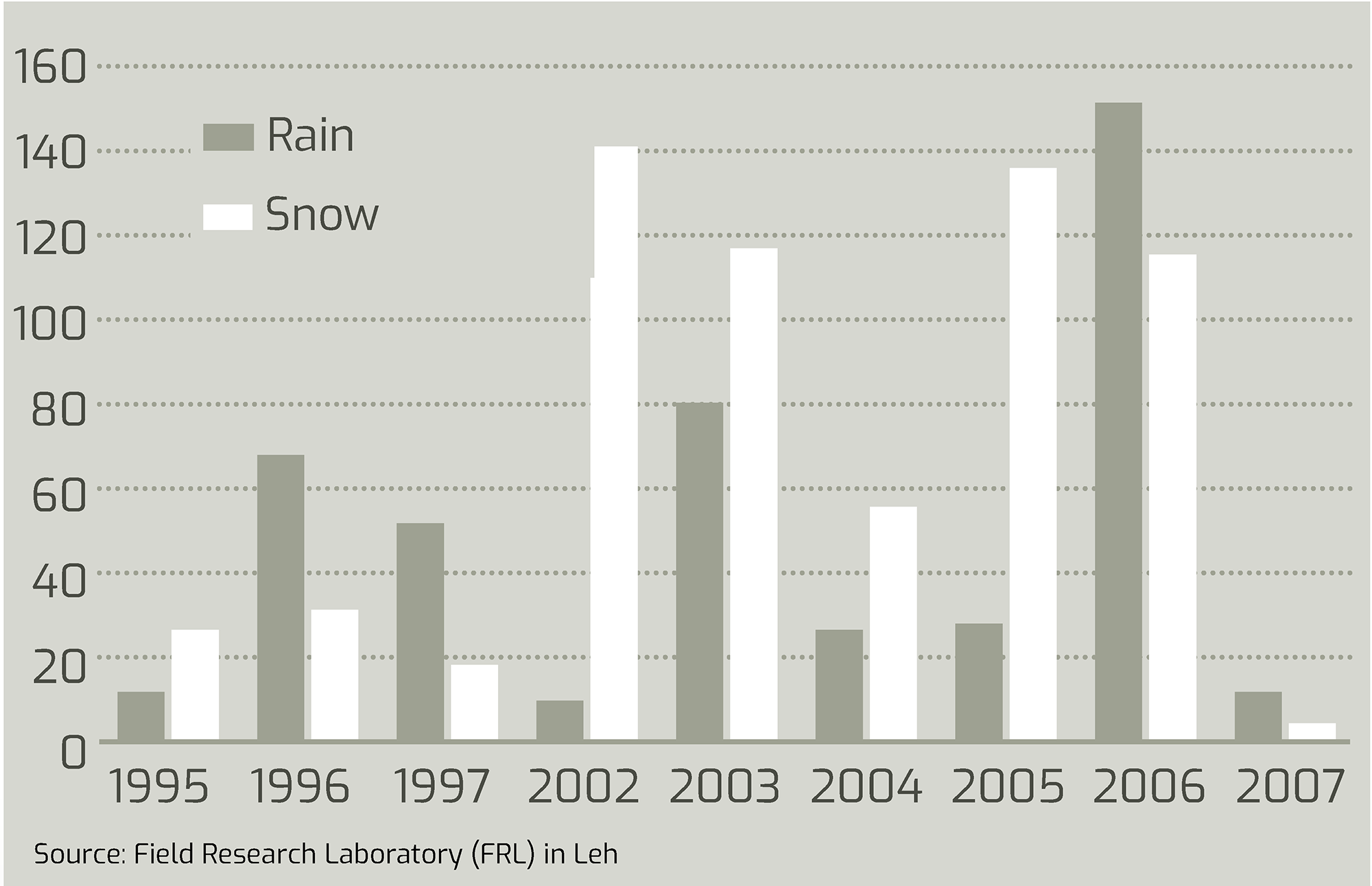

Ladakh is a cold desert, with precipitation limited to as few as two days per year. In the past 20–25 years, there has been a trend towards greater precipitation, but in a highly irregular pattern. For example, in 2002, there was almost no rainfall, but large quantities of snow. In contrast, precipitation totalling 150 mm was recorded in 2006, compared to an average of 32 mm between 1995 and 2007 (Field Research Laboratory in Leh).

Ladakh – water reporters

Ringchen A water reporter from Domkar

© CSEIndia

Ringchen, a water reporter from Domkar village, about 120 km from Leh: “In the past five years, we have observed more water in our streams during the summer months of July and August. There was so much more water that it was too much for the streams to hold it all, hence flooding occurred. At first we were puzzled, but after speaking with the elders, we were told that at the bottom of the glaciers at the top of the mountains there are very big lakes, which are frozen through the year, and water can only be seen in August. When we went up, we saw numerous small and big lakes which had little water due to the lake breach, but there were some with water. This showed us that snow is melting at a faster pace due to rising temperatures.

Action

The CSE Media Resource Centre (MRC) organised a workshop for journalists and water reporters in Leh (Ladakh) to draw their attention to the signs of climate change in this fragile ecosystem. The water reporters are villagers hand-picked from some of the villages around Leh, who have actively been learning about the recent changes in the weather patterns in their villages. In an attempt to train them as citizen reporters, the MRC designed a form for them to use in the field to conduct in depth research (see above). It serves as orientation for climate change issues, which have become a part of their lives. Above all, however, it serves as an aid in writing about the indicators and signs and engaging the public imagination. The Media Resource Centre seeks to impart basic writing skills, along with skills in documenting research in the field.